The Emergence Of The Gentle Birth Movement

Let’s take a brief look at the historical development of awareness around the birth process so that we can place Lotus Birth as part of a continuum of development in Western thought regarding childbirth.

Generally, the outcome of birth is parallel to life expectancy. Improvements in nutrition and sanitation and the understanding of infection have had the most dramatic effect on what are now regarded as better outcomes for mother and child. Child mortality has decreased and life expectancy continues to grow.

The historical context of birth

Up to the 1940s, birth had been the realm of midwives, and most babies were born at home. With the Industrial Revolution, thousands had moved to the cities to find employment. In the cramped city environments, much was changed from the community-oriented village existence. Women continued to become pregnant and babies were born; however, they were lacking the supportive environment experienced by previous generations.

Having babies traditionally is women’s business in all indigenous cultures, and was so in Western culture up until that time. The people building and managing cities were men, and men were making decisions about things they didn’t understand. To enable doctors to care more efficiently for the ill, they built hospitals – gigantic buildings full of the sick and dying. The hospital also became the place to which a woman had to go when she was about to deliver her baby.

People working in hospitals have a certain way of looking at things that enables them to identify what’s wrong with a person and how best to address the problem. This is appropriate when somebody presents with a problem. It is not a helpful attitude for a normal healthy birth. Birth thus became regarded as a series of wrongs that had to be righted.

Urbanisation and changing birth practices

The first lying-in hospitals were designed to give trainee doctors and obstetricians the chance to attend to women in labour and had very high mortality rates due to doctors’ ignorance of sepsis. By the 1950s all women found themselves ritually shaved, laid on their backs, strapped into metal stirrups, cut open and anaesthetised when all they wanted was to have a baby.

Modern birthing practices saw the mother arbitrarily drugged and the baby consequently delivered drugged and usually screaming or needing resuscitation. Large numbers of babies were dragged from their drugged mothers with forceps, their mothers never knowing the details of the birth or remembering much of it afterwards.

Brutally held upside down and hit on the bottom, the newborn was ‘welcomed’ into the world. This was followed by separation from the mother in a large room full of other babies, and by days of starvation, as the mother’s colostrum (first milk) was considered ‘useless’.

Most of us, if we were born in a hospital environment, were initiated into the world in this way. Today research on the brain patterns of sleeping babies – often regarded as ‘good’ babies – shows that they are like those of brains in shock.

The awakening to the birth experience

Gradually women, who up to that point had seen doctors as the experts knowing more about birth than they themselves did, began to stir from their apathy and take initiative. The 1960s saw a grassroots revolution as women began to practise mental, emotional and physical birth preparation, known as psychoprophylaxis. They learned to relax their bodies and consciously breathe through contractions while focusing their minds on a chosen focal point in the room.

Women delivering their babies free of drugs were talking about giving birth with joy and deep satisfaction. Fathers and friends made their way into the labour wards to support the birthing woman. Many and varied are the stories of how they were or were not received by hospital staff. Dr. Lamaze in France and Dr. Grantly Dick-Read in America became known for their support of this latest development in birthing practices.

Breastfeeding, which had fallen victim to the march of ‘progress’ via the multi-national formula companies, supported by the medical profession, began to return from its demise as women remembered the natural way of caring for their babies.

Rediscovering natural birth

The next leap in our evolution was a return to a more gentle birth. In 1967, Dr. Frederick Leboyer awoke the Western obstetrics world to the possibility that the baby was a feeling participator in the birth process.

In his book and film Birth without Violence, Leboyer brought attention to the sensitivity of the newborn and the impact of birth practices on the development of the child. Leboyer suggested that the baby’s screaming was indicative of distress and that the conditions into which the new members of society were being received be examined in the light of what was good for the baby.

Leboyer highlighted the violent way in which the newborn was treated when delivered in a modern hospital environment. Leboyer himself had delivered thousands of babies in the orthodox way. It was only after experiencing his own birth in primal therapy that he awoke to the impact birthing practices had on the baby. That moment of birth, a time of openness to the new, a time of lifeforming impressions, in his eyes was barbaric beyond belief.

Leboyer drew attention to the impact of drugs on the unborn child. The assault of cold air-conditioning on new, exposed skin, of bright lights on eyes opened for the first time, of clashing instruments and loud voices on ears used to the muffled sounds of underwater frequencies, of having the oxygen supply through the umbilicus severed before the supply of air to the lungs was fully established – all contributed to the trauma a newborn child experienced at birth.

The birth revolution continues

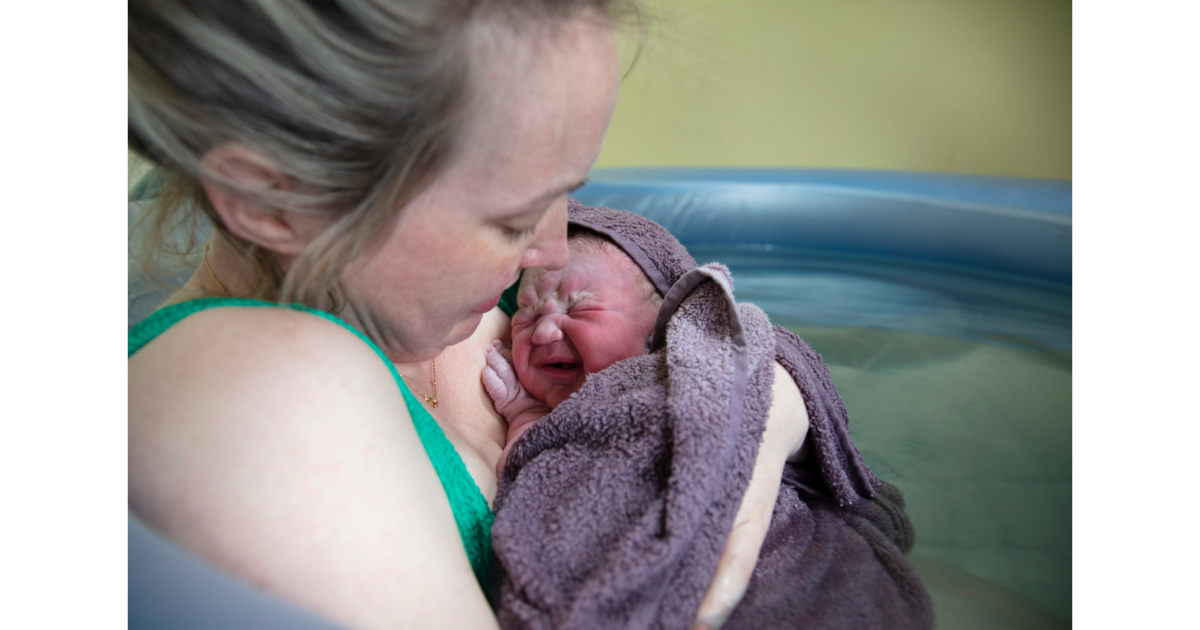

‘Birth without violence’ was his cry for reform. Leboyer advocated no drugs for the mother; soft lighting and warm air in the delivery suite; and a gentle delivery which included careful massage and floating the newborn in a tub of warm water. Having re-experienced in therapy the pain of having his umbilical cord cut, Leboyer insisted on leaving the cord attached until it stopped pulsing, usually twenty or more minutes after delivery, arguing that the blood that fills it belongs in the baby’s body. All who observed this method carried out were left in no doubt as to the beneficial impact on the newborn and the happy parents.

The Leboyer Method, as it became known, was welcomed by many parents who found supportive doctors to attend them. However, it was derided by many who found it much more satisfying to cut cords, drug women, cut them open and hear the scream of the newborn. This they considered as ‘normal’. Yet hospitals that provided Leboyer births found their bookings swell and knew they were on to a good thing. Some offered modified Leboyer births. Leboyer deliveries also thrived in the fertile home birth sector.

A movement for choice

Birth centres began sprouting everywhere. Sheila Kitzinger in the UK with her writings and appearances around the world inspired the notion of ‘woman-centred birth’.

In the 1980s water birth entered the picture. The Western world began to hear about Russian births, where the baby was born underwater. Startling photographs, and then film, showed how it was done. By then, the Russian experience was twenty years old. Many people felt an immediate resonance with this way of giving birth. Women found relief from the contractions in the supportive milieu of warm water. Women labouring in water found that it helped them enormously to relax, and reports of pleasurable, even ecstatic births were being heard. Babies made their entry from the womb into the warm waters of spas, tubs and baths. This new phase showed us that the ‘facts’ we believed and were taught about the newborn were full of inaccuracies.

In France, Michel Odent was becoming renowned for natural, instinctive births, many underwater. Those who had never attended one had plenty to say about what they hadn’t experienced; however, Michel Odent became the champion of a woman’s right to birth her baby naturally.

There was also what Janet Balaskas in the UK popularised as Active Birth – when a woman takes control of the positions she uses to birth her baby, and her caregivers adapt to her needs. This has been a powerful influence on birthing practices in more recent times. During all of these developments, she was awakening: she, who inhabits and expresses through the female form, was claiming her own process. Women were listening to their bodies and their babies in utero, knowing how their babies wanted to be born.

Lotus Birth: A return to natural birth

Lotus Birth is part of this awakening. Lotus Birth is a call to pay attention to the natural physiological process. Its practice, through witnessing, restores faith in the natural order. Lotus Birth extends the birth time into the sacred days that follow and enables the baby, mother and father and all family members to pause, reflect and engage in nature’s conduct. Lotus Birth is a call to return to the rhythms of nature, to witness the natural order and to the experience of not doing, just being.